Using Gitlab CI to Build Your R Package

What is R?

R is a statistical computing and graphics language developed in the early 90’s, which is widely used by data scientists and analysts. It is also a language that is core to Persado’s machine learning platform (in addition to Python). Like many other languages, R has a package management system, used to build and share libraries of code. These are equivalent to gems in Ruby, modules in NodeJS, and packages in Python. In order to build these packages, you would adhere to a certain folder structure and run the R CMD build <package_root_folder_path> command in your terminal. The end result is a compressed (tar.gz) file containing your library that can be consumed by a compatible R environment, typically by running the command R CMD install <path_to_compressed_file>. When you are working with an internal team, manually compiling a package on your local machine and sharing it via normal communication channels (email, Slack, etc.) is not a very effective manner of tracking, documenting, and securing versions of your package, especially if they contain proprietary machine learning algorithms. This is where a continuous integration environment comes into play.

What is Gitlab CI?

Gitlab is Persado’s source code management platform of choice. It is essentially a self-contained solution that provides project management, Git repository hosting, a private Docker repository, CI/CD pipelines, Kubernetes integration, and a host of other things we don’t need to worry aboout for the context of this post. What we care about most are the CI/CD pipelines. Continuous integration is the practice of monitoring your source repository via a central server (Gitlab, Github, Bitbucket, etc.) and triggering a series of actions when changes are detected. Some of these actions can include compilation of code, deployments, and (most commonly) running automated test suites. To utilize the CI pipelines in Gitlab, you’ll first need a Gitlab runner process. If you use the hosted solution at Gitlab.com, a Gitlab runner process is provided for you in every plan, including the free tier. However, if you self-host your Gitlab service, then you will need to also create and host your own Gitlab runner process. Our team uses a hosted runner with the Docker executor.

How can we use them together?

With a Gitlab runner in place, we can start putting it to use by having it compile our R package for us and making it available to others via a central location. To get started with the CI pipeline, we need to add a .gitlab-ci.yml file in the root folder of our git repo. Our instructions below assume you are also using the Docker executor for your runner process.

Let’s take a look at what our final .gitlab-ci.yml file would look like, and then walk through it line-by-line:

stages:

- build

build R package:

stage: build

image: r-base:3.6.1

artifacts:

name: "R-pkg-$CI_COMMIT_REF_NAME-$CI_COMMIT_SHORT_SHA"

expire_in: 1 yr

paths:

- "*.tar.gz"

script:

- cd $CI_PROJECT_DIR

- R CMD build $CI_PROJECT_DIR

We start off by defining the high-level steps called “stages” in our pipeline. By default, if you exclude the list of stages, it assumes a single default stage named test. Since test is not an accurate representation of what we are doing here, we override the default by defining a single stage named build. Each stage contains one or more tasks, known as “jobs”. In this case, we only have a single job named build R package that will run as part of the build stage.

stages:

- build

build R package:

stage: build

image: r-base:3.6.1

Within this job, we tell Gitlab that the job belongs to the build stage, followed by what Docker image we would like to use as the environment to run our scripts in using the image key. This docker image can be hosted in your private Gitlab repository or from Docker Hub, which is where we are retrieving r-base:3.6.1 from.

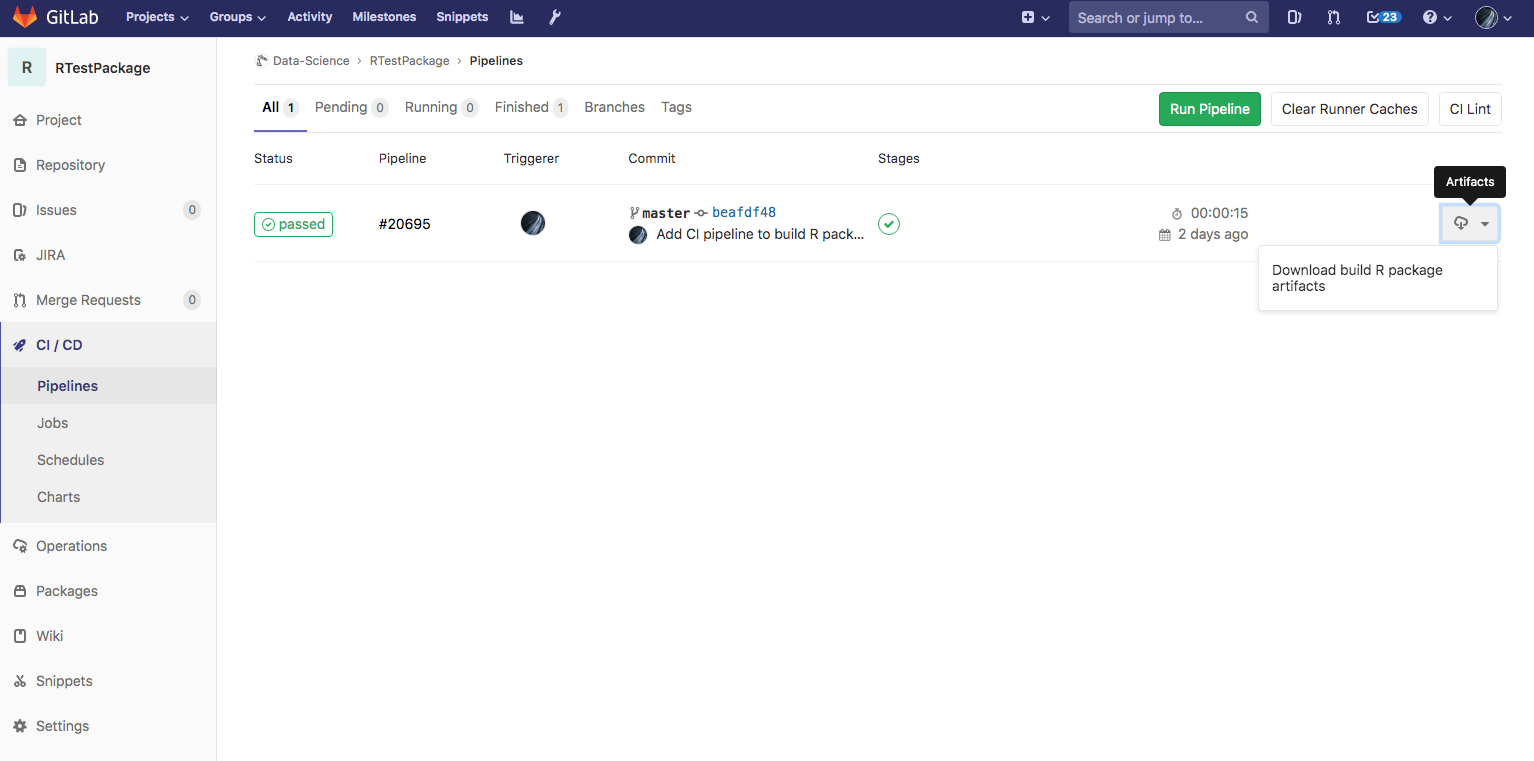

Next up, we define what the “artifacts” of our pipeline job should be. An artifact is one or more files that are created when running a job that you would like to keep around after the job is done, such as test coverage reports, compiled binaries, or our built R package. When the job is done running, these artifacts are automatically uploaded to Gitlab, which can store them either in a local directory or S3. These artifacts can then be downloaded via the Gitlab UI as a zip file.

artifacts:

name: "R-pkg-$CI_COMMIT_REF_NAME-$CI_COMMIT_SHORT_SHA"

expire_in: 1 yr

paths:

- "*.tar.gz"

When we define an artifact, we have the option to provide a name that will be used for the creation of the zip file, which by default is named artifacts.zip. Within the name key, we are telling Gitlab to name it with a prefix of R-pkg- followed by 2 environment variables that Gitlab provides within the pipeline environment, which represent the sanitized name of the git branch (CI_COMMIT_REF_NAME) and a shortened commit hash (CI_COMMIT_SHORT_SHA). A full list of the variables provided by Gitlab in the pipeline environment can be found here with descriptions. We also tell Gitlab to keep these artifacts available for download for 1 year, which overrides Gitlab’s default of 30 days. This value will change depending upon your needs, and if you find yourself surpassing the alloted time but still needing the artifacts, you can always rerun a specific pipeline execution to regenerate it.

The final key is defining the list of files that qualify for uploading as an artifact using the paths key. Since our repo does not contain any files with a .tar.gzip extension, and we know that the final file will, we can safely tell Gitlab to consider any file with this extension an artifact. By default R will dynamically name the final compressed R package file using the Package name and Version number from the DESCRIPTION file, such as mypackage_2.0.1.tar.gz.

This brings us to the final part of our .gitlab-ci.yml file, the script key, which is a list of sequential shell commands that the job is comprised of. These are the actions that define your job and its success or failure. If any of the commands on this list finish with a non-zero exit status code, the job will consider itself as having failed. his in turn will mark your entire CI pipeline as failed. In our script, we first change into the directory given to us by Gitlab via its CI_PROJECT_DIR environment variable. This is the directory where our copy of the source code from git for this pipeline lives. NOTE: This is very important, as Gitlab can only detect and upload an artifact if it is present in this directory, so any files or folders listed under the artifacts:paths key are relative to the location of this directory.

script:

- cd $CI_PROJECT_DIR

- R CMD build $CI_PROJECT_DIR

Finally, we run the R CMD build command and pass in the CI_PROJECT_DIR environment variable as an argument to tell it where to find the files that define the R package we wish to build. This command will output the R package to your current directory, which in our case is the same folder so that Gitlab can detect it as an artifact.

Here’s what the final result would look like in the Gitlab UI:

With this file in place, every time you push a change to Gitlab, the CI pipeline will detect and compile a freshly R package that you can download from the UI and have a record of over time. You can now grant members on your team access to your project so that they can download the compiled package as well!